Key takeaways: Tannins structure wine, influencing its texture, color, and aging potential. They come from grape components and oak barrels during aging. Their role is essential: mouthfeel structure, color stabilization, and natural preservation for aging. On the palate, they create variable astringency depending on the grape variety and winemaking.

👉 Two concrete examples: Château Marsyas Rouge, whose ripe tannins support beautiful depth and great aging potential, and Acústic Celler Braó, where more prominent but elegant tannins structure an intense and generous wine.

Have you ever been surprised by that dry sensation in your mouth after a sip of red wine? Tannins, natural compounds from skins, seeds, or oak barrels, are responsible. These polyphenols structure the wine, influence its color, and determine its aging ability. They vary by grape variety: Cabernet Sauvignon offers powerful tannins, Pinot Noir more silky notes. Less present in white wines (direct pressing) or rosés (short maceration), they soften over time, becoming smooth and elegant. Discover how these molecules influence your wine choice.

- Wine tannins: what are they and where do they come from?

- Learning to recognize tannins in your glass

- The winemaker's art: how winemaking shapes tannins

- The secret of great wines: the evolution of tannins over time

- Tannins and health: separating fact from fiction

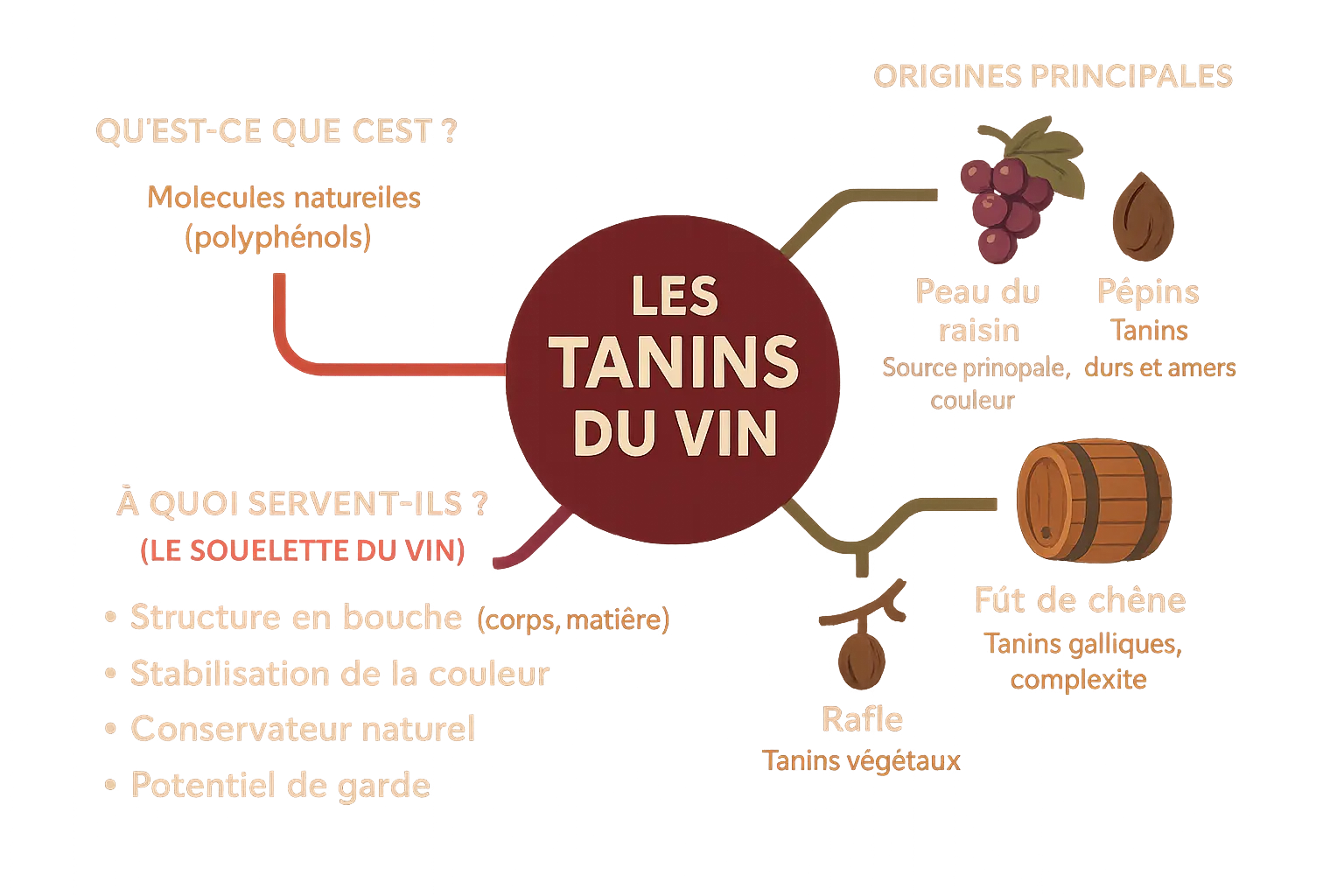

Wine tannins: what are they and where do they come from?

Behind the word "tannin," a natural molecule

Tannins are polyphenols, molecules present in many plants. They're found in heavily steeped tea, fresh walnuts, or even tree bark. On the palate, they cause a sensation of dryness, sometimes roughness. It's not a taste per se, but a texture that stimulates the mucous membranes. In wine, these compounds play a central role, far beyond this tactile impression.

The two main origins of tannins in wine

They come from two distinct but complementary sources. First, the grape itself, through its solid parts. Then, the wood of barrels used for aging. This dual origin enriches the wine's complexity.

- Grape skin: the main source of tannins and color for red wines.

- Seeds: they contain tannins that are often harder and more bitter.

- Stems: the "framework" of the bunch, which can provide vegetal tannins if retained during winemaking.

- Oak barrel: during aging, the barrel wood slowly releases its own tannins (gallic tannins) to the wine, contributing to its complexity.

The wine's skeleton: what do tannins really do?

Tannins form the backbone of wine. They provide structure, body in the mouth that balances aromas and acidity. By stabilizing pigments, they also influence the color of red wines.

Their role as a natural preservative is crucial. By capturing free oxygen, they slow oxidation and extend the wine's lifespan. This is why tannin-rich wines, like certain Bordeaux or Burgundies, can age for decades. Without them, aging potential would be much lower.

Learning to recognize tannins in your glass

Astringency: that unmistakable dry sensation

Tannins cause a rough sensation in the mouth by reacting with saliva proteins, without being a taste in the strict sense.

"Astringency is the signature of tannins on the palate. It's not a taste, but a tactile sensation, a slightly rough caress that coats the palate and gives the wine all its structure."

It evokes black tea or green walnut, distinct from acidity or bitterness.

From red to white: do all wines have tannins?

| Wine Type | Typical Tannin Level | Main Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Red Wine | High | Long maceration of skins, seeds, and stems. |

| White Wine | Very low to none | Direct pressing without skin contact. |

| Rosé Wine | Low | Limited contact (a few hours) with skins. |

| Orange Wine | Medium to high | White wine vinified with skin maceration. |

From rough to silky: a matter of grape variety

Cinsault offers light tannins, while Cabernet Franc presents fine and elegant tannins. Varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon or Nebbiolo reveal powerful tannins, contrasting with the velvety texture of Pinot Noir.

The winemaker's art: how winemaking shapes tannins

Tannins are not simply present in wine, they are precisely shaped through age-old techniques. The winemaker, a true artisan of taste, masters each step to reveal the hidden potential of the grapes.

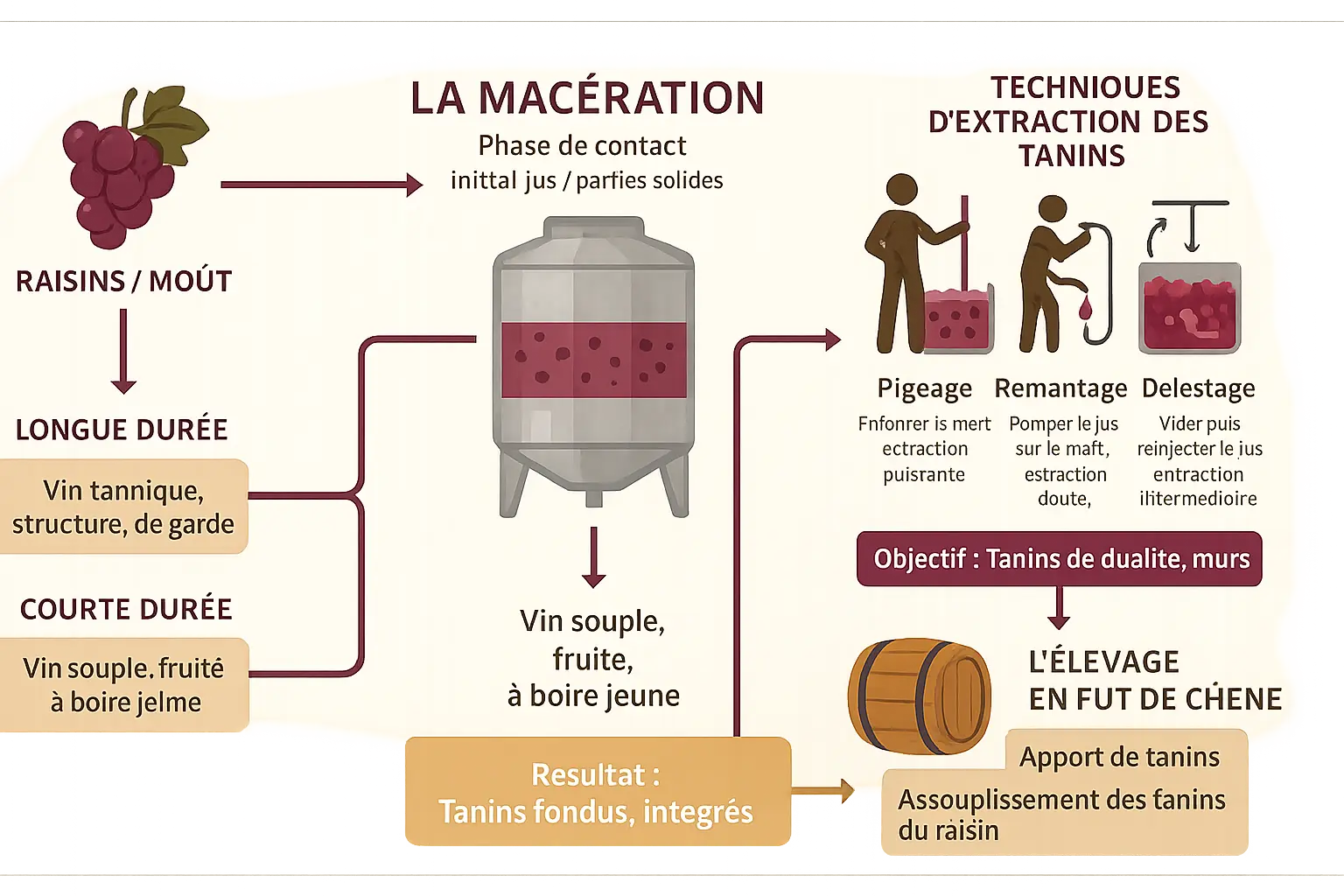

Maceration: the key moment of extraction

During maceration, the juice comes into contact with the solid parts of the grape. This step determines the wine's structure. Short maceration produces supple, fruity wines ready to be enjoyed quickly. Conversely, extended maceration releases more tannins, creating complex wines destined to age.

Punching down, pumping over: precise techniques for quality tannins

Extraction methods directly influence tannin quality. Here are the key techniques:

- Punching down (pigeage): a traditional technique where the "cap" (floating skins and seeds) is pushed down into the juice. It's a powerful and qualitative extraction, often done manually.

- Pumping over (remontage): a gentler method that involves pumping juice from the bottom of the tank to spray over the cap, promoting gradual extraction.

- Rack and return (délestage): an intermediate technique that empties the tank before reinjecting the juice onto the cap, ensuring complete saturation.

The influence of oak barrel aging

Oak barrel aging transforms tannins. The wood contributes its own compounds while facilitating micro-oxygenation that softens the grape tannins. This process creates smooth tannins, perfectly integrated into the wine's structure. A fine example of elegant and supple tannins, where the oak is finely melted, can be found in Aurora Cabernet Franc 2018.

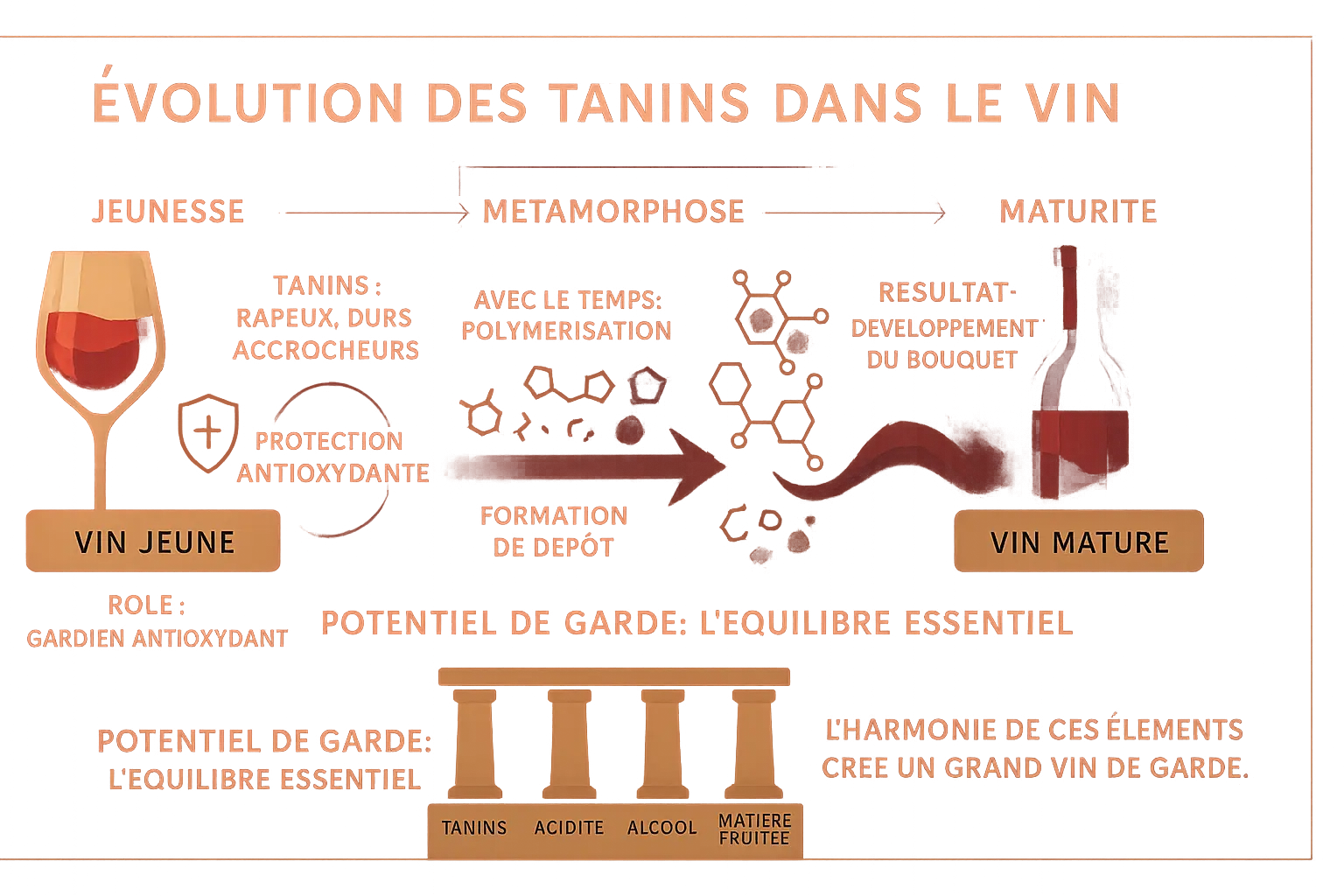

The secret of great wines: the evolution of tannins over time

Tannins, guardians of time and shields against oxidation

Tannins protect wine from oxygen through their antioxidant role. They allow wine to develop complex aromas over the years, rather than oxidizing. This power explains why tannic wines, like certain Bordeaux, age for several decades. For example, a Cabernet Sauvignon from Médoc gradually reveals notes of leather and truffle, while its firm tannins soften. This phenomenon is accentuated when the wine is aged in oak barrels, where wood tannins add to those from the grapes to reinforce structure.

From youth to maturity: the metamorphosis of tannins

In a young wine, tannins can seem harsh or aggressive. Over time, they unite (polymerization), become heavier, and form sediment. Those in suspension become silky or velvety. This process transforms a Barolo from Piedmont, initially powerful, into a wine of remarkable elegance after several years. A wine like Château Musar Rouge 2017, with already supple tannins, promises harmonious evolution.

"Time is the best ally of great tannic wines. It polishes their edges, transforms their vigor into elegance, and their youthful astringency into a caressing and silky texture."

Knowing when to wait: how to evaluate aging potential?

Wine aging relies on a balance between tannins, acidity, alcohol, and fruit matter. Acidity stabilizes, alcohol provides body, and fruit nourishes tertiary aromas. An imbalance, such as powerful tannins but absent fruit, blocks aging. The harmony of these four elements determines the wine's ability to evolve long-term. Thus, a Sauternes ages exceptionally thanks to its sugar-acidity balance, despite its low tannins. Conversely, a wine too light in acidity, even rich in tannins, risks becoming flabby with age.

Tannins and health: separating fact from fiction

The benefits of tannins: an asset for health?

Tannins, polyphenols present in grape skins and seeds, are often associated with antioxidant effects. These molecules could help fight free radicals, responsible for oxidative stress linked to aging. However, their bioavailability remains limited: a portion is metabolized by the liver before acting in the body. Studies suggest a link between moderate polyphenol consumption and improved cardiovascular health, but these results still need confirmation. Their primary role in wine remains structural, providing firmness and complexity to tasting.

Headaches and red wine: are tannins really to blame?

While 10% of consumers sensitive to tannins report headaches after a glass of red, the majority of headaches are linked to other factors. Sulfites, often blamed, concern less than 1% of allergic individuals, and their concentration in wine is much lower than in dried fruits. Biogenic amines, such as tyramine or histamine, produced during malolactic fermentation, are more likely culprits. Finally, alcohol content, which causes vasodilation, or rapid consumption without hydration, plays a central role. The cocktail effect of these elements, combined with fatigue or lack of sleep, explains most discomforts.

How to choose wine according to your sensitivity to tannins?

To limit astringency, prefer wines made with low-tannin varieties: Gamay (as in Beaujolais), Pinot Noir (Burgundy), or Cinsault (southern France). Red wines aged in barrels or bottles have tannins softened by slow oxygenation, which promotes their polymerization. Also opt for cuvées described as having pleasant and soft tannins. White or rosé wines, less extracted, are a suitable alternative. Finally, serve wine at a moderate temperature (16-18°C): wine that's too warm accentuates the perception of tannins.

Tannins, architects of wine, derived from plants, structure with astringency and aging potential. From skins and wood, they sculpt cuvées, evolving for unique textures. Understanding tannins means grasping great wines and choosing according to your taste.